By Craig Tinashe Tanyanyiwa

It was the sort of experiment that might have seemed audacious just months earlier: can you organise a hackathon entirely in the Wetskills spirit, without compromise or shortcuts, by merging the spontaneity of virtual collaboration with the connective power of an in-person finale? In late October, as delegates gathered in Lusaka for the 26th WaterNet/WARFSA/GWP-SA Symposium, the answer became unmistakable. Yes, you can. And when you do, something remarkable happens.

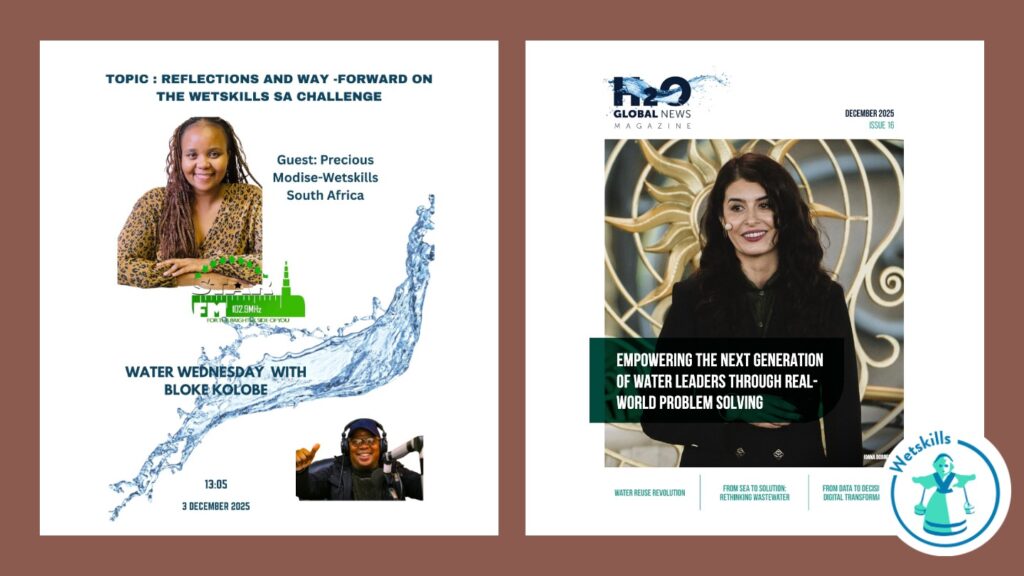

The Wetskills Water Innovation Hackathon marked the first hackathon of its kind between Wetskills Foundation and the Water Research Commission of South Africa. The partnership, formalised through a Memorandum of Understanding, has now extended into an ambitious new format that proves both organisations are willing to innovate on their own methodologies.

A Cohort Like No Other

The sixteen participants who joined this five-week journey came from South Africa, with one from Zimbabwe and another from Nigeria. Among them were ten women and five men, illustrating a sector increasingly energised by female leadership. Six participants were sponsored through the WRC-Wetskills partnership; the remaining ten joined via WRC’s separate collaboration with WaterNet, broadening the reach of both networks in a single effort.

What unites Wetskills participants is not homogeneity but hunger. A hunger to tackle real problems, think beyond convention, and do so in teams that push you far beyond your comfort zone. This cohort carried that hunger into two tangible challenges. One focused on Improving Youth’s Access to Opportunities in the Water & Sanitation Sector, the other on Innovative Revenue Collection for Rural Municipalities. The case owners, Thabo Mthombeni and Dr. Mamohloding Maahlo from WRC, did not present these as academic exercises. These were live problems owned by senior practitioners, demanding genuine solutions.

Five Weeks of Pressure and Progress

From October 2 to October 23, the programme took place through weekly four-hour virtual sessions held via Microsoft Teams every Thursday evening. Each 120-minute session focused on a different aspect of innovation: team dynamics, action planning, project management, business development strategy, pitching excellence, and technical paper writing. Supervisors collaborated with teams throughout, not as judges but as guides, helping them improve teamwork and test their solutions until they were truly ready for evaluation.

This is where Wetskills philosophy resides: not in providing answers, but in creating conditions where teams find their own answers through guided, rigorous work. The virtual format became an advantage. Teams from three countries could work almost in real-time. The Thursday sessions established rhythm, accountability, and a weekly checkpoint where teams could realign, and supervisors could step in precisely when pressure was necessary.

The Convergence: From Screens to Stages

But Wetskills has always recognised that the screen is a tool, not a replacement. That is why the final act had to be face-to-face. From 29 to 31 October, as the WaterNet Symposium gathered in Lusaka, the sixteen young professionals travelled there. Not as spectators, but as key participants in a live innovation forum.

Teams presented their concepts, each supported by a Business Model Canvas and complemented by poster displays and technical papers. The winning team received top honours for their work on Improving Youth’s Access to Opportunities in the Water & Sanitation Sector. Zintle Pretty Mbeka, Anothando Yono, Rolivhuwa Mulovhedzi, and Vumile Dudu Sekele developed a solution that addressed a vital challenge: how do we create genuine pathways for young people into meaningful careers in the water sector? Their approach will now progress from concept to pilot with institutional support and momentum.

The Human Element

What isn’t visible in the program notes or photographs is perhaps the most important: the relationships built between young professionals and the senior practitioners, policy makers, and technical experts attending the symposium. A young woman from South Africa working on rural revenue innovation found herself in conversation with a municipal representative. A Nigerian participant identified potential collaborators from three countries.

But there was another aspect to those three days. The gala dinner, where the line between “professional event” and “celebration” completely dissolved. Teams danced. Participants from different nations discovered common ground not through case studies but through music and laughter. Friendships formed. The kind that, in a sector as interconnected as water management, often becomes the foundation for future collaborations, partnerships, and innovations. These were authentic human connections made in a convivial space that professional conferences rarely foster.

Beyond Lusaka

The hackathon expanded the partnership’s geographical reach and enhanced engagement with regional water sector governance platforms. By linking innovation activities to a major continental symposium, the event increased youth visibility within senior policy and technical forums. Participants from South Africa could connect with peers and leaders from across Southern Africa. The four solution concepts are immediately applicable to challenges throughout the region, not just South Africa.

For WRC, this demonstrated that its role has evolved from a national research institution to a genuine facilitator of regional innovation. For Wetskills, it validated that the organisation’s methodology works not only as a pressure-cooker two-week format but also as a flexible framework that can be extended over five weeks, incorporating both virtual and in-person phases, while maintaining its core strengths: real problems, diverse teams, a rigorous process, and direct engagement with decision-makers.

The hackathon is over. Participants have returned to their respective countries and institutions. However, the four solution concepts remain active. This is how innovation advances in the water sector. It occurs not when government or companies develop grand strategies but when a diverse group of young people, invested in their work, are presented with real problems, given five weeks of structured thinking, and provided with a platform where their efforts reach those capable of acting.

Lusaka in late October was not just hosting another conference. It was showcasing the moment when regional water governance realised that the next generation of solutions will not originate from any single organisation or country, but from teams that transcend borders, genders, and disciplines. As long as they are given the right conditions, the right problems, and the right audience.

Lusaka in late October was not just hosting another conference. It was showcasing the moment when regional water governance realised that the next generation of solutions will not originate from any single organisation or country, but from teams that transcend borders, genders, and disciplines. As long as they are given the right conditions, the right problems, and the right audience.